New book in the works

I handed in a new book manuscript yesterday. It's called (for now): Breaking News, The Courageous Women Reporters Who Turned Journalism on its Head, and it's YA nonfiction telling the stories of "girl stunt reporters." It also includes writing exercises and Q&A interviews with investigative reporters. I’m excited to have it out in the world—probably in early 2027.

NEW! Chrysalis Audiobook

Now listeners can learn Maria Sibylla Merian’s story in audiobook form.

Ever since it was first published, I’ve wanted an audiobook version of Chrysalis, Maria Sibylla Merian and the Secrets of Metamorphosis, so Merian’s story could reach a wider audience. Now there is one. With beautiful narration by Amélie Trufant Dawson, the new format allows listeners to immerse themselves in the dawn of the Scientific Revolution and the lives of artists, naturalists, and early entomologists as they try to make sense of the world.

It is available on Audible, among other places.

Here’s a sample. Enjoy!

Women’s History Month 2023—Events

Check out the Events page for information about readings and signings tied to the paperback release of Sensational: The Hidden History of America’s “Girl Stunt Reporters” on March 21, 2023. Fortuitously, this is in the middle of Women’s History Month, the perfect time to be celebrating intrepid female journalists from the nineteenth century. In-person events will take place at Mrs. Dalloway’s in Berkeley on March 29, Elliott Bay Books in Seattle in March 30, and Village Books in Bellingham on March 31.

If you are interested in the role of “girl stunt reporters” in the history of, not just journalism, but creative nonfiction, check out the interview “Who Created Creative Nonfiction?” at Essay Daily. Rachel May, author of An American Quilt: Unfolding a Story of Family and Slavery and an associate professor at Northern Michigan, and I had a wide-ranging discussion about, among other things, what Tom Wolfe and Truman Capote owe Nellie Bly.

What’s Her Name Podcast Features Maria Sibylla Merian

The excellent women’s history podcast What’s Her Name featured Maria Sibylla Merian in a recent episode and included an interview with me about Merian’s exceptional life, her contributions to ecology, and the book Chrysalis, Maria Sibylla Merian and the Secrets of Metamorphosis.

Here’s the description from What’s Her Name: “Germany was still burning witches when Maria Sibylla Merian daringly filled her 17th-century home with spiders, moths, and all kinds of toxic plants. Bold choices saved her from accusations of witchcraft–and from a mundane life. Merian’s fascination with metamorphosis led her all the way to the rainforests of South America, where she recorded countless new species, 130 years before Darwin!”

Listen (and see a wonderful collection of Merian artwork) here.

Sensational Selected as a Minnesota Book Award Finalist

Sensational: The Hidden History of America’s “Girl Stunt Reporters” has been selected as a finalist for the 2022 “Minnesota Books Awards” in the General Nonfiction category. It’s in excellent company, alongside Booth Girls: Pregnancy, Adoption, and the Secrets We Kept by Kim Heikkila, Find a Trail or Blaze One: A Biography of Dr. Reatha Clark King by Kate Leibfried, and The Violence Project: How to Stop a Mass Shooting Epidemic by Jillian Peterson and James Densley.

Check out the full list of finalists here and keep an eye out for the awards ceremony and announcement of the winners on April 26, 2022.

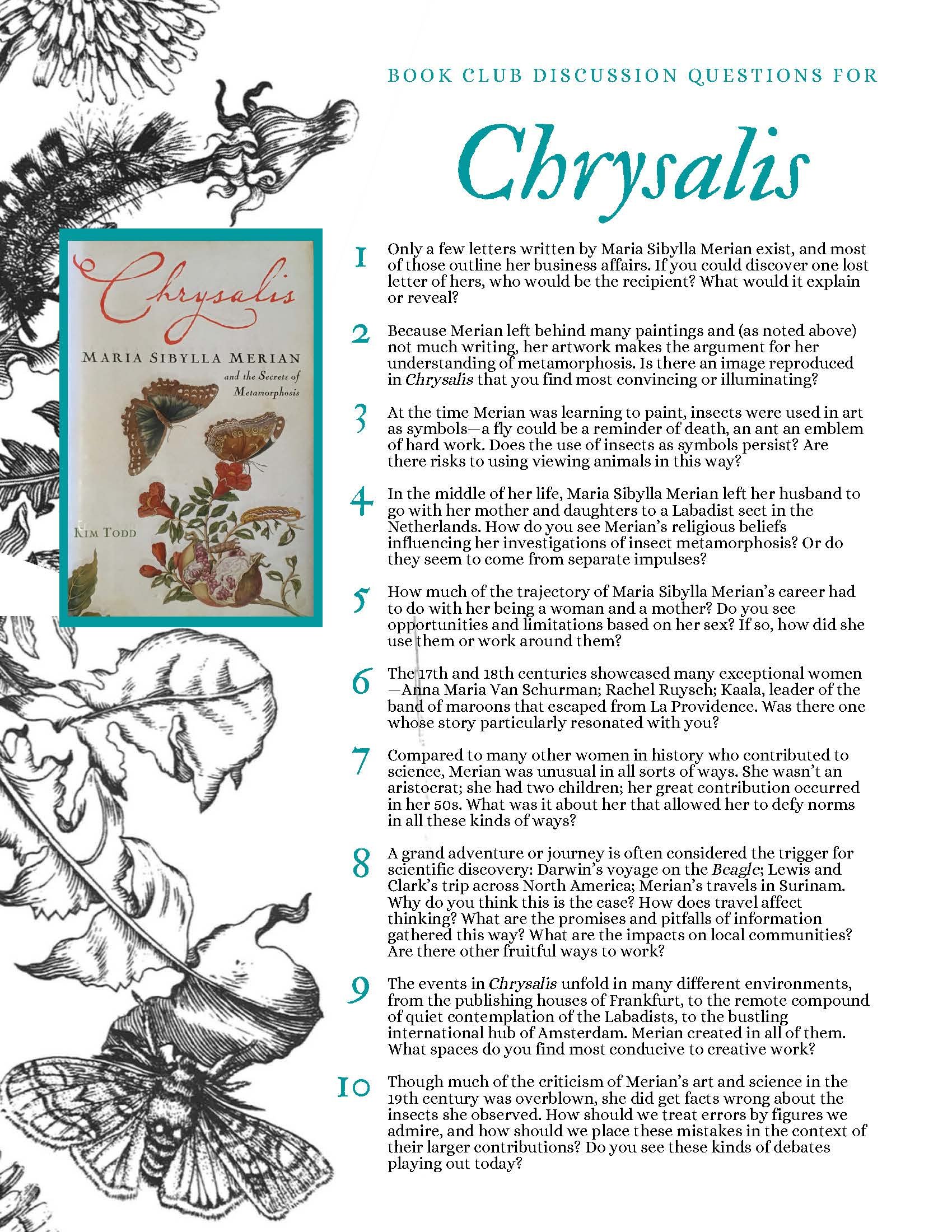

Book Club Discussion Questions for Chrysalis

Here are a few book club discussion questions for Chrysalis, Maria Sibylla Merian and the Secrets of Metamorphosis. Feel free to contact me if you would like a printable PDF. I’d be happy to send one your way.

Book Club Discussion Questions for Sensational

Here are a few book group discussion questions for Sensational, The Hidden History of America’s “Girl Stunt Reporters.” Contact me if you would like a printable PDF. I’d be happy to send it on.

Quick Video Interview on “Girl Stunt Reporters”

Jezebel created a video on “girl stunt reporters” as part of their “Rummaging Through the Attic” series.

Jezebel produced this 3.5-minute interview about Sensational: The Hidden History of America’s “Girl Stunt Reporters” as part of the “Rummaging through the Attic” series. Topics covered included individual journalists, what’s wrong with the wholesale dismissal of “yellow journalism,” and the origins of the book cover. The interviewer also let me sum up my take-home message this way: “When you see people denigrating writing specifically by women as frivolous or not serious or sentimental . . . we should always meet that criticism with a question.”

Sensational Reviews

“Sensational, A Hidden History of America’s ‘Girl Stunt Reporters,’” has received some generous press attention in the few weeks since its release.

The New Yorker took a deep dive into the subject of “The Lost Legacy of the Girl Stunt Reporter:” “In general, the girl reporter practiced an immersive, novelistic craft, deploying warmth, suspense, humor, and an instinct for plot. Society was inclined to view her as lacking in reason, and so she painted with the senses, seducing naysayers with a vivid, intimate voice.” The Wall Street Journal said, “Ms. Todd’s resurrection of these courageous reporters is fascinating because the women and their stories are so vibrant.” The Library Journal noted, “Todd’s comprehensive account rightly sheds light on the many women who changed the face of journalism and helped jump-start the newspaper industry. Her accessible writing draws in readers from the first page.” According to Publishers Weekly, the book “makes clear the crucial role female reporters played in pioneering investigat[ive] journalism and boosting progressive reform movements.”

Of the audio book, read by Maggi-Meg Reed, AudioFile magazine declared, “This is a terrific pairing of an impressive work of nonfiction and a splendid performer.”

A Few Sensational Interviews

Recently, I had the chance to talk with John Maynard of the Freedom Forum on the First Five Now program. We delved into 19th-century stunt reporters, their undercover investigations, and the multi-pronged efforts to censor their findings. Watch it here.

Also, host Jonathan Small and I discussed Nellie Bly’s ebullient prose style, the evolution of nonfiction narrative, and other vital topics of the 1890s and today on his podcast Write About Now. Check it out.

Deborah Kalb’s book blog featured a Q&A about Sensational, where we covered some of the misunderstanding about these early journalists and their work. Read all about it.

The Authors Guild also highlighted my work in a Member Spotlight and gave me space to talk about what writing means to me and techniques for overcoming writer’s block. Here you go.

I loved talking with biographer William Souder (Carson, Audubon, Steinbeck) at a Barbara’s Bookstore event, putting stunt reporters in context of the New Journalism of the 1800s, as well as the mid-1900s. Listen in.

Early Female Journalists Sparked Movement Toward Workplace Justice

An recent issue of the Star Tribune featured my op/ed about the way journalists of the 1880s and 1890s covered sexual harassment. The piece begins:

“In Minneapolis in 1888, 21-year-old reporter Eva McDonald slipped onto the floor of the Shotwell, Clerihew and Lothmann factory on the banks of the Mississippi, where hundreds of women hunched over long tables, sewing calico shirts and overalls.

The room was reeking and hot. The company had just slashed wages to pennies a day. But the women saved their anger for the foreman's corrosive contempt for his female employees.

If he met them dressed nicely on the street, he sneered that if they could afford such finery, he should cut their wages more. He offered to trade one woman's promotion for sexual favors, shook and swore at another.”

Read the rest here.

Women’s History Month—Undercover Women

For Women’s History Month, I’m highlighting female journalists who went undercover.

The first of Nellie Bly’s asylum articles in the World, October 9, 1887.

For Women’s History Month, I’m highlighting female journalists who went undercover, those covered in Sensational: The Hidden History of America’s “Girl Stunt Reporters” and others. Pseudonyms and hidden identities were common for women writers in the nineteenth century. Some used them sparingly; some never emerged from their disguises.

First up—Nellie Bly.

“I write the truth because I love it and because there is no living creature whose anger I fear or whose praise I court.” Nellie Bly launched the stunt reporter genre when she when she faked her way into Blackwell’s Insane Asylum for Women in 1887 for the World.

Her narrative voice—funny, down-to-earth, self-deprecating—drew readers in and kept them coming back for more. Her blazing career made other women think reporting was just the kind of work they were looking for.

Illustration in the World of Nellie Bly plotting to get in to Blackwell’s Asylum.

Next, Eva McDonald Valesh (pseudonym: Eva Gay).

“The city workshops teem with abuses, and upon them the Globe proposes to throw the broad light of day.” In 1888 the St. Paul Globe touted reporter Eva McDonald who slipped into mattress and shirt factories to interview women working long hours for pennies.

Part reporter, part activist, McDonald encouraged women to stand up for themselves. As she did. She gave rousing speeches, interviewed a president, and quit editing Samuel Gompers’ magazine when he refused to credit her work.

An Eva McDonald article in the St. Paul Globe, April 8, 1888.

Then comes Winifred Sweet.

“The man’s cruelty seemed so wanton and unprovoked that I really feared he would strike as I lay there.” Winifred Sweet, alias Annie Laurie, mock fainted on Market Street in San Francisco in 1890 and uncovered vicious treatment of poor women at the public hospital.

An adventure-seeker who first tried life as an actress, Sweet (later Winifred Black, later Winifred Bonfils) investigated poisonous cosmetics and dressed as a man to be the first reporter on the scene of the Galveston hurricane. The stage’s loss was journalism’s gain.

Winifred Sweet (Annie Laurie) launches her public hospital reporting in the San Francisco Examiner on January 19, 1890.

Illustration in the Examiner of Winifred Sweet giving an interview subject a skeptical glance.

In the 1890s, Victoria Earle Matthews exposed sham agencies in the South that lured Black women north, promising jobs only to trap them. “Let women and girls become enlightened, let them begin to think, and stop placing themselves voluntarily in the power of strangers,” she said in a lecture.

Gathering a group of like-minded activists, Matthews would wait at the docks in Manhattan, trying to catch these young women before they could be hoodwinked, finding them jobs, connecting them with relatives, offering them a place to stay and access to a library stocked with books by Phillis Wheatley and other Black authors.

Illustration of Victoria Earle Matthews in The Journalist in 1889.

One of the most scandalous exposés was that of the “Girl Reporter” of the Chicago Times.

“It used to be the dream of my childhood that I would some day become a writer—a great writer—and astonish the world with my work,” she wrote. In 1888 the “Girl Reporter” feigned pregnancy and asked doctors for an abortion. Her revelations in the Times shook the city.

The Girl Reporter charted abortion techniques and gave details of prescriptions, providing “a medical education” that made readers deeply uncomfortable. Then vanished. I spent many hours in the archives trying to trace her steps while writing SENSATIONAL.

The Girl Reporter gets down to business for the Chicago Times in December, 1888.

And who could forget Nell Nelson?

“[W]hen a foul-smelling, overheated, ill-ventilated, ratty fire-trap is regarded as an ideal workshop…the time has come for action.” Even before recording sexual harassment in factories for the Chicago Times in 1888, Nell Nelson was noted for wielding a “particularly caustic pen.”

Sewing shoes, assembling feather dusters—Nelson (real name: Helen Cusack) started out posing as a job applicant at Chicago businesses before moving to New York. Her work inspired the Illinois Factory Law and convinced New York State to hire female factory inspectors.

The Chicago Times had a hit with Nelson’s 1888 series and promoted it relentlessly.

Ida B. Wells wrote during the 1880s, 1890s, and far beyond.

“[I]n me they seemed to see somebody who had come to help them in their trouble.” A legendary anti-lynching reporter, Wells pretended to be a relative to interview condemned men in an Arkansas jail in 1920.

Through these conversations, Wells uncovered the truth of the deadly “riot”—that the jailed men, mostly sharecroppers, had been trying to organize to keep more of the money from their crops, when they were attacked by whites concerned about losing their profits. In her books Southern Horrors, A Red Record, and The Arkansas Race Riot, she did what no one else was willing to do: count the lynchings, investigate the causes, expose the hypocrisy.

Illustration of Ida B. Wells in The Journalist in 1889.

Time to ponder Eliza Putnam Heaton.

“I think I shall always be a better American citizen for my emigration.” In 1888, reporter Eliza Putnam Heaton embraced a challenge deemed too dangerous for Bly—she traveled from Liverpool to the U.S. in steerage, documenting the experience of European emigrants.

Her account, subtitled “A Sham Emigrant’s Voyage to New York,” introduced readers to a bevy of interesting and hopeful newcomers. She concluded: “This is still the land of promise.”

Heaton’s story appeared in the 1888 Brooklyn Times Union, among other places.

One of the most irrepressible stunt reporters was Caroline Lockhart.

“Haven’t I been drinking moxie all spring?” If Nellie Bly could do it, why couldn’t she? That was the logic of Lockhart who had many adventures, in disguise and out, for the 1890s Boston Post, including donning a diving suit to explore the harbor.

Caroline Lockhart investigates the fish for the Boston Post in 1895.

Less than a year after Bly went into the asylum, the Chicago Tribune hired Eleanor Stackhouse.

The paper wasn’t shy about promoting her work, teasing readers by asking, “Where has Nora Marks been?” A more apt question might be where hasn’t she been? Eleanor Stackhouse (alias “Nora Marks”) went from employment agencies that promised women jobs to meat-packing plants in her 1880s-1890s reporting for the Tribune.

Nora Marks was “not idle surely” as she roamed Chicago on behalf of the Chicago Tribune.

Ada Patterson, whose career was rich in stunts, was known as “Nellie Bly of the West.”

In one example, (more “women underwater” than “women undercover,” but I love this image too much not to post it), Patterson tested out a submarine for the New York Journal in 1897.

Ada Patterson goes deep for the New York Journal in 1897.

Elizabeth Banks was known for bringing American-style reporting to London.

“It really would appear that regular hours from eight to six would be much better for all concerned,” she wrote after her trip undercover into the damp life in a commercial laundry in the mid-1890s. Her book, Campaigns of Curiosity, was a hit on both sides of the Atlantic.

By her own admission, she was nobody’s heroine, but she attacked hypocrisy wherever she found it.

Elizabeth Banks in her mid-1890s book, Campaigns of Curiosity: Journalistic Adventures of an American Girl in London.

In 1963, Gloria Steinem launched a 20th-century stunt.

“Today I put on the most theatrical clothes I could find, packed my leotard in a hatbox and walked to the Playboy Club.” Steinem went undercover as a Playboy Bunny for Show Magazine and revealed that the promised glamour was an illusion.

In the first of two installments, Gloria Steinem describes applying to the Playboy Club for Show Magazine in 1963.

Tips for Keeping a Field Journal

Prompts for getting started observing and writing about the natural world.

Over the years, I’ve taught a number of workshops on keeping a field journal. It’s a great way to get outside, clear your mind, and learn about where you are. The 20 minutes suggested below might be a long time for wintery day, depending on where you are. Adjust as temperatures and blizzards permit. Here’s how to get started.

Tools (Most are optional):

Notebook with unlined paper

Writing utensils: pen, colored pencils

Field guides

Magnifying glass

Ruler

Camera

Binoculars

First: Find a spot that appeals to you, where you can spend 20 minutes.

Second: Document where you are. Note the day, time, location, weather, and something you experience with each of your five senses.

Third: Use one of the following prompts and start writing.

1) Observe an animal (or, if you can't find one, a plant). Keep it in sight or hearing as long as you can. What is it doing? What does it remind you of? How does it interact with other parts of the landscape? Can you identify it? Do you need a sketch to help you look it up later? Alternatively, look for and record all the places you think an animal might have been. Can you find a evidence of chewing or nesting? A feather? A path?

2) Record the landscape at three different scales. Look at the big picture (Imagine you are looking from a plane, for example. Can you find evidence of geology? How does water move? How does topography shape settlement patterns? How it this place situated in time? What did the landscape look like 100 years ago? A thousand?); scan the mid-range (This is roughly a human scale. What are dogs doing? Crows? What happens on top of the traffic lights or in stairwells? How is the land configured and used maybe thirty feet around you?); then study an object or organism (not human built) very closely. (Find something—a pinecone, a leaf, a moth wing—that can fit in your palm and observe it intimately.) How does your experience of the world change at each scale?

Fourth: Write three questions about your observations.

When You Get Home: Revisit your notes. Flesh out moments and observations that you didn't have time to do justice to in the field, identify plants and animals you were unsure about, color in your sketches, try to answer your questions.

Repeat as Desired.